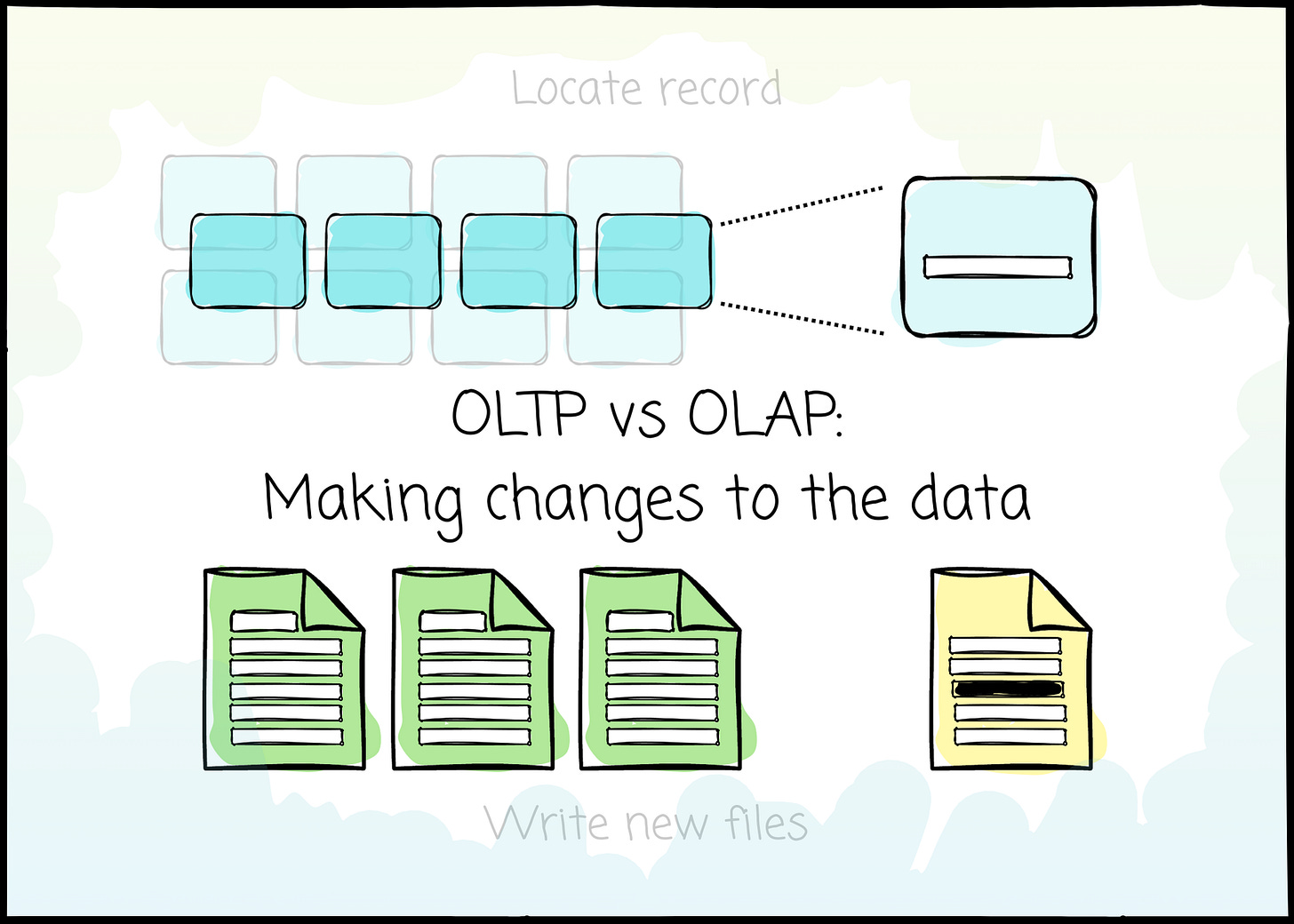

OLTP vs OLAP: Making changes to the data

In just 15 minutes, you will understand the difference in how they handle writing, updating and deleting the data

I will publish a paid article every Tuesday. I wrote these with one goal in mind: to offer my readers, whether they are feeling overwhelmed when beginning the journey or seeking a deeper understanding of the field, 15 minutes of practical lessons and insights on nearly everything related to data engineering.

Intro

Business users need to observe what is actually happening. When does the user buy a book? When a driver finishes the trip. Why don't users use this feature, and how does a competitor win that market?

We, as data engineers, collect, store, and prepare data to help them achieve that purpose. However, the data is not static; it is added, updated, and deleted to align with real-life events. Handling data changes is crucial.

In this article, we will see how OLTP and OLAP relational databases handle data mutation.

Since the physical data mutation is implemented differently depending on the database, this article presents only the idea of common approaches. For a detailed implementation of the database, refer to its official documentation.

OLTP

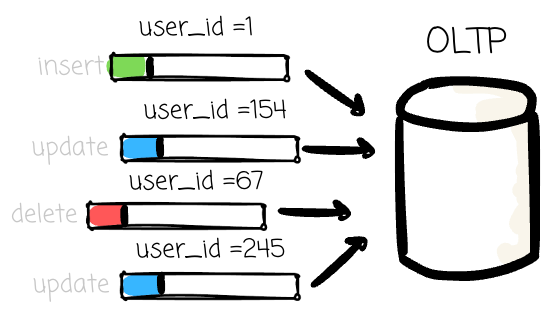

OLTP systems primarily handle ingesting new information; their data operations typically read/write/update a small amount of data each time. They power everything from ATM transactions and e-commerce orders to inventory management.

Their primary objectives (not comprehensive) are:

High Concurrency: To support thousands of users and processes simultaneously reading and writing data without interfering with each other.

High Throughput for Writes: To quickly process a large volume of minor, frequent updates, inserts, and deletes.

So, the way they manage the data changes is optimized for a small number of rows. From the previous article, we know that most OLTP systems manage data in a row-store format. In more detail, an OLTP relational system, like PostgreSQL, stores row data side by side in pages

Page

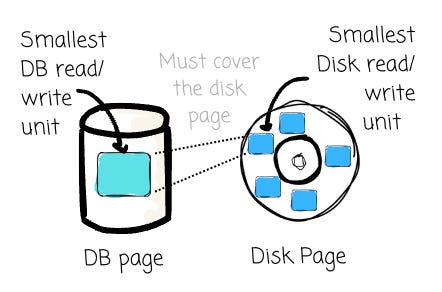

A database page is a unit of storage created and managed by the database software itself. This is different from the disk page, which is a unit of storage managed by the disk hardware.

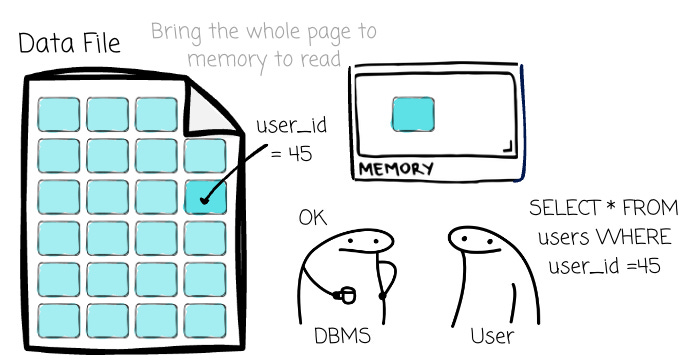

A database page is the fundamental unit of I/O for a DBMS. When the database needs to read data, it doesn’t fetch a single row from the disk; it reads the entire page containing that row into memory. Likewise, when it writes data, it writes the whole modified page back to disk.

The page’s size varies depending on the database. It is typically a multiple of the disk block size, e.g., 8 KB in PostgreSQL. A page contains metadata, actual data, or indexes, and usually it doesn’t include a mix of data types (e.g., a page for data only or a page of indexes only). Each page will have a unique identifier from the database. There is mapping (depending on the database implementation) to help the database find the physical location of a page.

Typically, pages are organized in heap files, which store a set of pages in random order. The database also has a mechanism to determine the number of pages in a file and which one still has available space to store more data (it is a special page called a directory page, but we won’t discuss it in more detail here).

Keep in mind that the smallest unit of read and write is a page. Next, we will examine how data is organized on a page and explore how data mutation works.

Tuple-oriented

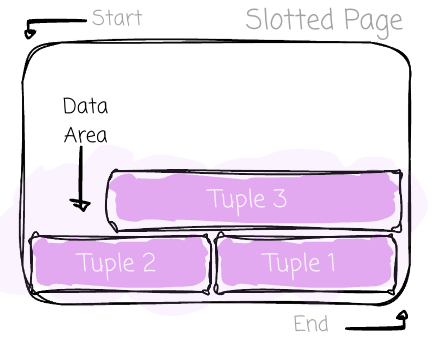

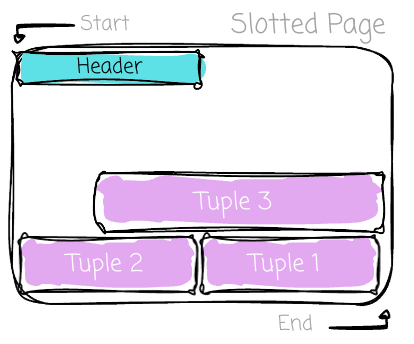

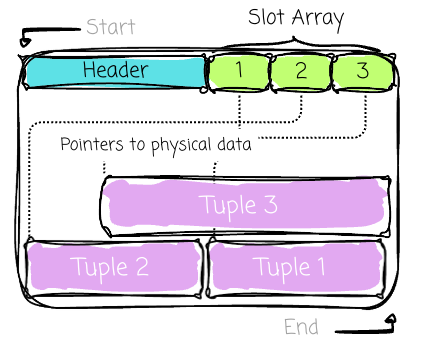

The common sense “storing the row data right next to each other “ usually makes us think rows (tuples) are simply appended from the beginning to the end. In fact, there is a more robust scheme to store data. Most SQL OLTP databases use the slotted page (here are the details from PostgreSQL). It’s a fixed-size page with four main areas: the header, the slot array, the free space, and the data area:

Tuples will be first added at the end of the page and stacked toward the beginning of the page. Tuples can vary in size. Each will have a unique identifier and a header. Metadata, such as the map for null values or information used for transaction and concurrency control, is stored in the header. The space where tuples reside is typically referred to as the data area.

At the beginning of the page, there is a header. It contains metadata about the page, which allows the DBMS to quickly understand the page’s contents without scanning the data. Key metadata includes the number of slots currently in use in the slot array, pointers to the end and start of free space, ...

Then comes the slot array. Each contains the pointer to the beginning of an associated row in that page. In contrast to the data, a slot array will be added as an item and grow toward the end of the page.

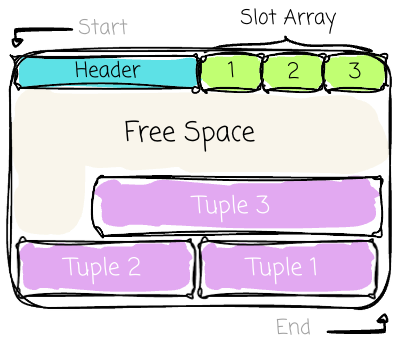

The space between the data and the slot array is free space for new data. As new tuples are inserted, a new slot is added to the slot array, and the tuple data is added to the data area, causing the free space to shrink from both sides. A page is considered full when the slot array and the data area meet.

What is the motivation behind this design? We don’t just append the data from the beginning to the end. Its main advantage is the ability to separate the logical (slot) and physical addresses of the tuples.

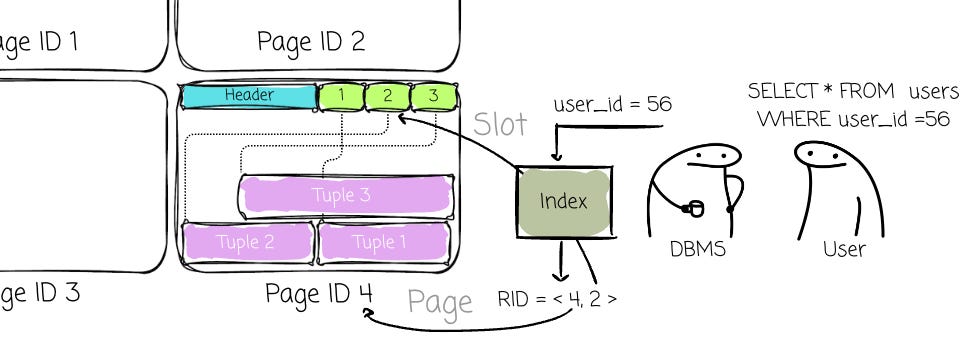

A row (tuple)’s unique address of a record (commonly referred to as Record Identifier (RID)) is not its physical byte offset. Instead, it is a composite key ⟨Page ID, Slot Index⟩. (Database can use indexes such as B+Tree to help find the RID faster.)

The PageID directs the DBMS to the correct page on disk, and the SlotIndex (or slot number) provides an index into the Slot Array on that page. The slot provides the final pointer to the record’s current physical location within the data area.

This allows the DBMS to move record data freely within the page

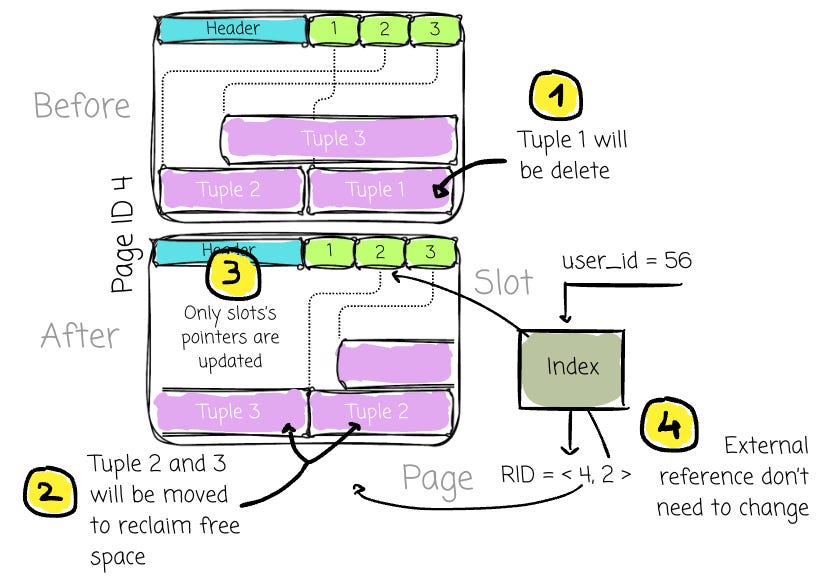

For example, when compacting the data to reclaim free space, the data needs to be moved; the only update required is to the pointers (that pointed to the physical location of the data) stored in the slots themselves.

External structures (e.g., indexes) can retain these stable RIDs without concern that they will become invalid when the physical data is reorganized.

Note: the data reorganization is inevitable, as data rows can be deleted at any time, and free space needs to be reclaimed to prevent fragmentation.

If a DBMS uses the physical location of the tuple for the RID, it must frequently update the RID whenever the data is moved, which is clearly inefficient.

After knowing how the data is stored in a slotted page, let’s find out how the data mutation is implemented.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to VuTrinh. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.