My name is Vu Trinh, and I am a data engineer.

I’m trying to make my life less dull by spending time learning and researching “how it works“ in the data engineering field.

Here is a place where I share everything I’ve learned.

Not subscribe yet? Here you go:

Intro

Browsing Medium, LinkedIn, Twitter, or any data engineering forum, you will see something like this: "Rust will replace Python in Data Engineering."

Rust has the community's attention, with many open-source projects like Polars, DataFusion, and RisingWave, alongside numerous tutorials demonstrating tasks previously efficiently done only with Python, now being accomplished with Rust more safely (as they claim).

I initially intended to let the hype pass and remain loyal to Python.

But I failed.

I couldn't resist the FOMO.

So, I started learning Rust.

This is not only an opportunity for me to learn something new (Rust) but also a chance to revisit something I've known for a while (Python).

This article is my first note on this journey, representing my effort to understand the difference between how Python and Rust manage memory.

Stack and Heap

The stack and the heap are parts of memory available to your code to use at runtime, but they are structured differently. Before diving into how Python and Rust free unused memory, let’s revisit Stack and Heap.

Stack

In memory management, the stack is crucial in structuring how values are stored and accessed during runtime.

This last in, first out (LIFO) mechanism ensures efficient data handling: new values are added to the top, and removal happens in the reverse order.

When your code calls a function, the values, including potential pointers to heap data and local variables, get seamlessly pushed onto the stack. The stack's structure indicates that all data stored here must have a known, fixed size.

The stack offers faster data access than the heap due to its organization. Since the location for new data is always at the top, no searching is required, making the pushing process faster.

However, the fixed-size constraint can be limiting, leading us to explore the heap for more dynamic memory needs.

Heap

Conversely, the heap provides a more flexible memory storage solution.

When data is allocated on the heap, a request for a specific amount of space is made. The allocator then locates an appropriately sized empty spot, marks it as in use, and returns a pointer indicating the memory location.

This process, known as allocating on the heap, contrasts the stack's pushing mechanism.

While the pointer to the heap has a known, fixed size, the actual data in heap retrieval requires following the pointer, much like finding a house following the address.

While heap allocation allows for data of unknown or changing sizes, it demands more effort from the allocator. Searching for an appropriate space and performing necessary bookkeeping (“Hey, this space is reserved; please look for other space”) for future allocations, which might be a slightly slower process compared to the stack.

Trade-off

Read/Write

Allocating space on the heap is slower than pushing to stack because the allocator needs to find space to hold the data/

Accessing data in the heap might be slower because we need to follow the pointer to locate actual data.

Space

Stack: fixed-size constraint

Heap: More flexible memory management

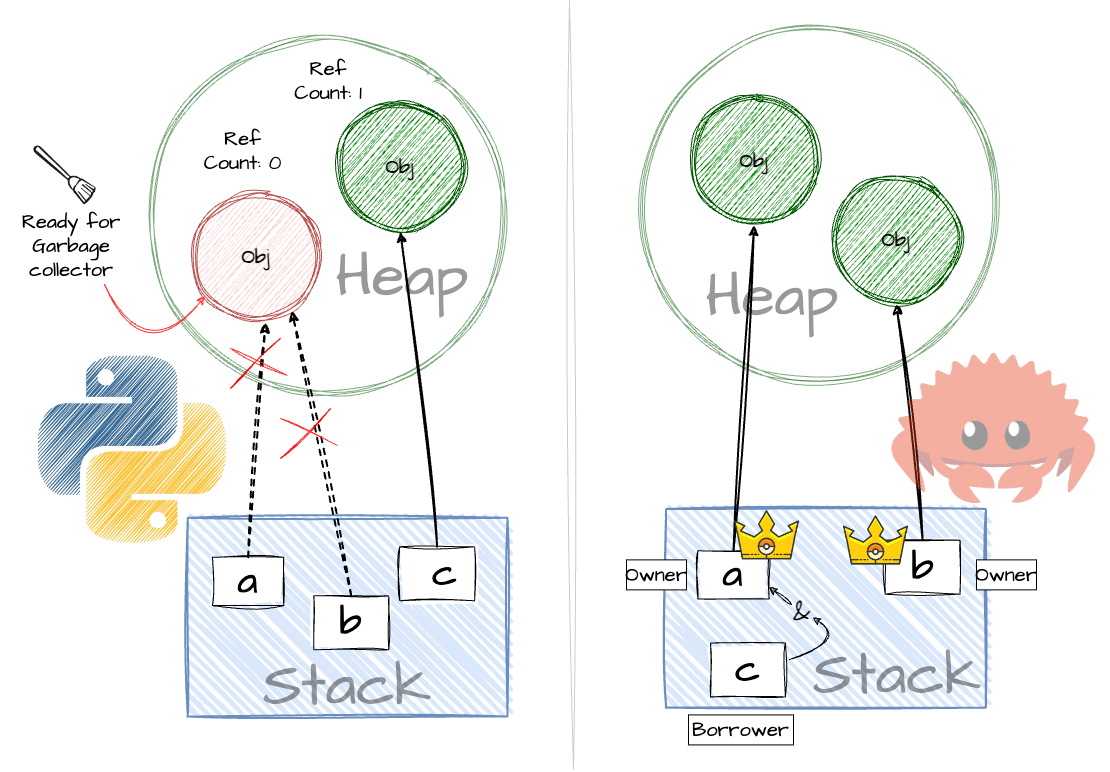

Garbage Collector in Python

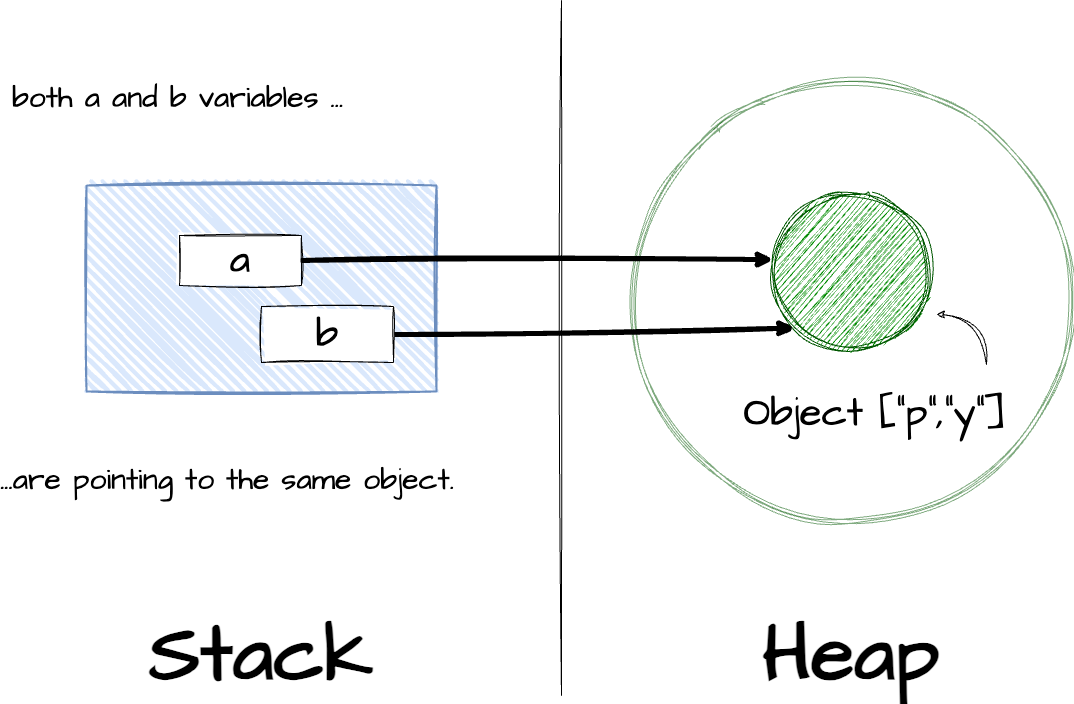

Everything in Python is an object.

Python variables do not actually contain the data; it is just the container holding address (pointer) which points to the location of the actual data object (in heap memory)

For a better way to think, variables are labels with names attached to objects.

Let's look at an example:

a = ["p","y"] #(1)

b = a #(2)

Create object

["p","y"]in heap memory and bind a to this object which means a will hold reference to object["p","y"]Careful here, when we define b = a, we do not copy the object

["p","y"]and bind it to b, b=a means now b will point to the same object of a which is["p","y"]

After knowing the fundamental relationship between variable and object data in Python, now it’s time to discover how Python manages memory for us.

In CPython, the primary algorithm for garbage collection is reference counting.

(I mention CPython here because other implementations like Jython, IronPython, and PyPy will have different algorithms)

Essentially, each object keeps count of how many references point to it. The object will be garbage-collected as soon as that ref count reaches zero.

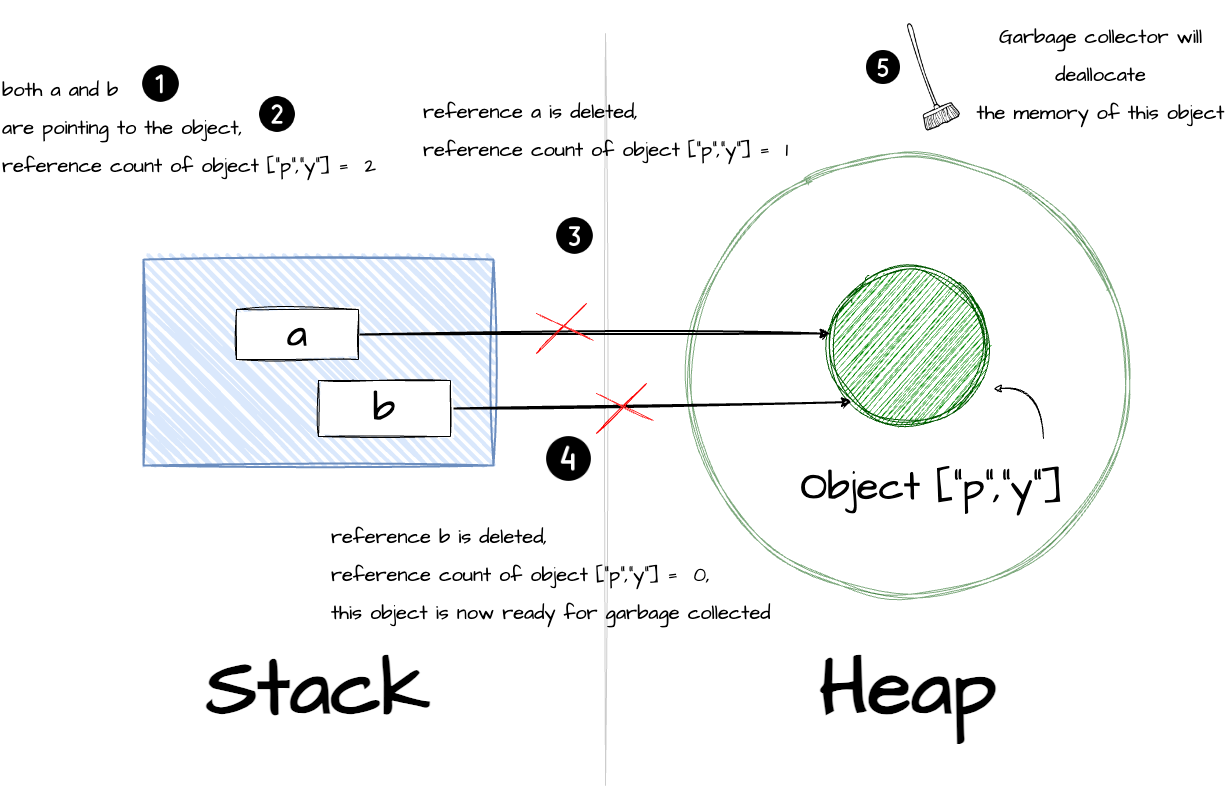

Let’s go back to the previous example:

a = ["p","y"] #(1)

b = a #(2)

del a #(3)

del b #(4)

Create object

["p","y"]in heap memory and bind a to this object which means a will hold reference to object["p","y"]

Reference Count for

["p","y"]: 1b will point to the same object of a, which is

["p","y"]

Reference Count for

["p","y"]: 2The

delstatement deletes the referencea, which meansawill not point to object["p","y"]anymore.

Reference Count for

["p","y"]: 1The

delstatement deletes the referenceb, which meansbwill not point to object["p","y"]anymore.

Reference Count for

["p","y"]: 0→ Object

["p","y"]is ready for garbage-collector

The process of garbage-collector automatically runs in the background, which means you don’t need to care or think about it; this feature is one of the things that makes Python friendly for users to write code with it.

You can manually control this process using the GC module if need

In this section, I mention the main idea behind CPython’s garbage collector. From CPython 2.0, a generational garbage collection algorithm was added to detect circular references; you can read more here.

Now, let’s see how things are done in Rust.

Ownership in Rust

Ownership

Ownership in Rust to make memory safety guarantees without needing a garbage collector.

It is a set of rules that govern control a Rust program manages memory.

Here are the rules:

Each value in Rust has an owner.

There can only be one owner at a time.

When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

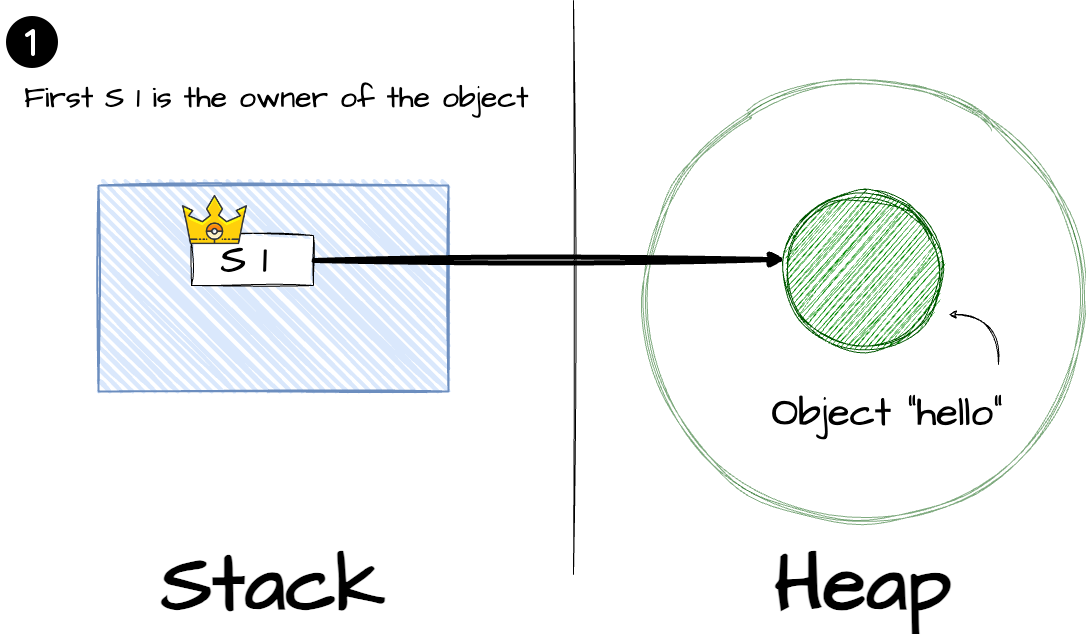

Let's apply these rules for better understanding:

{ // (1)

let s1 = String::from("hello"); // (2)

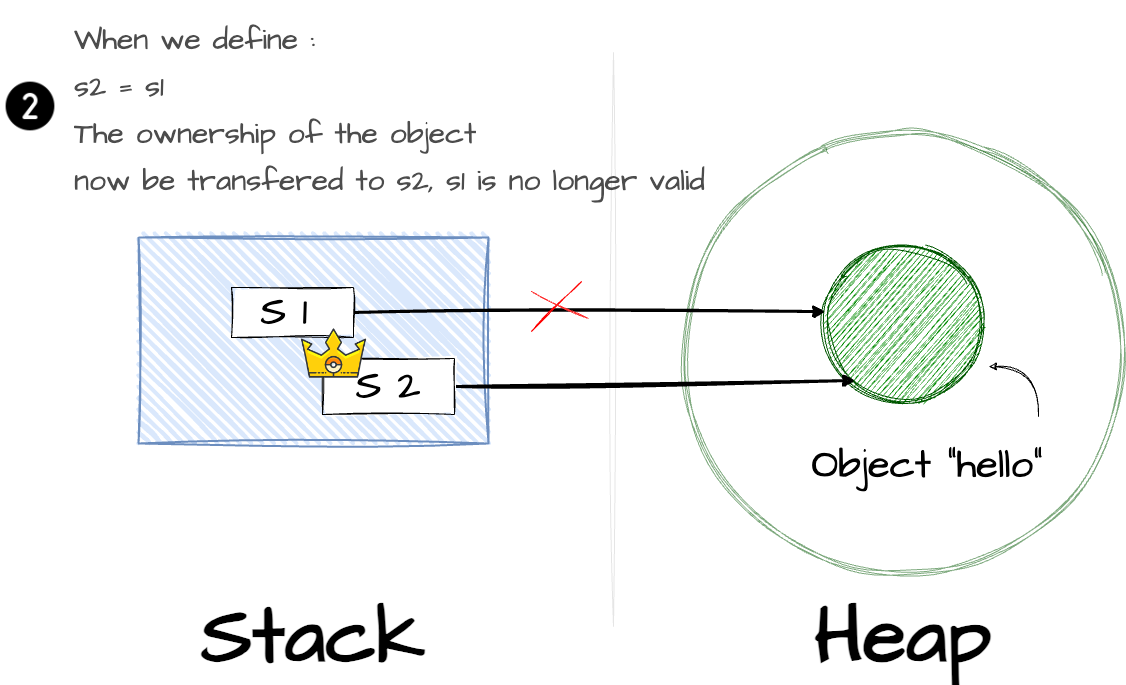

let s2 = s1; // (3)

} // (4)

s1is not valid

s1is now valid and be declared as the owner ofString::from("hello")

s2is now the owner ofString::from("hello")→ Due to the rules that only one owner at a time,

s1is no longer valid.

s2isnow invalid because it is going out of scope.

Some illustration:

Reference

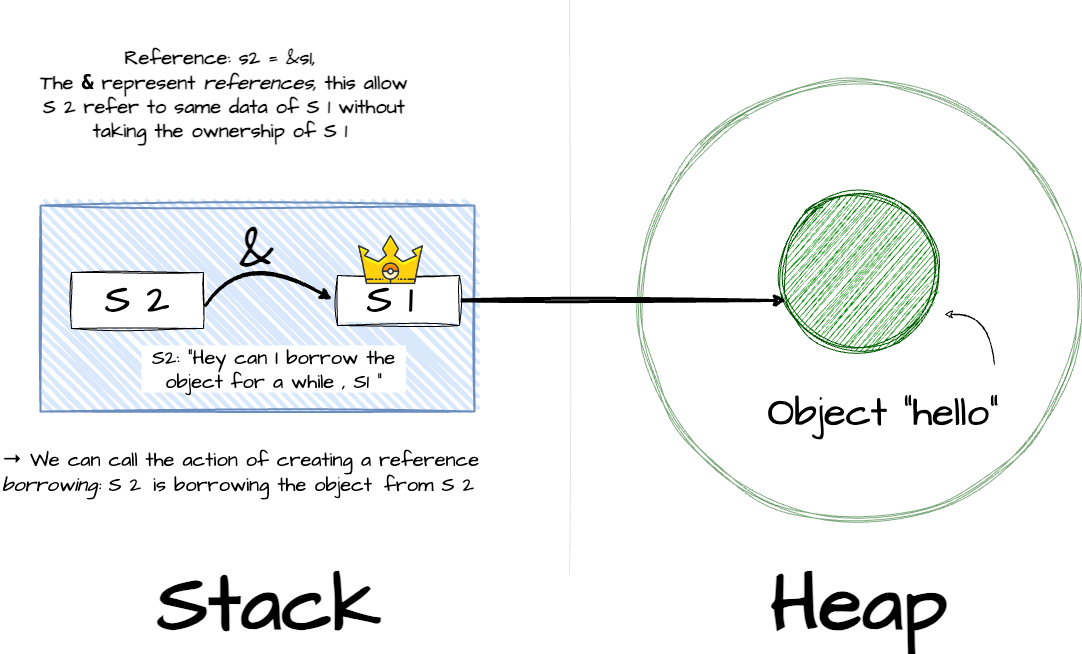

Due to the rule that only one owner for the object at a time, Rust introduces the concept of Reference.

Said, Reference is a pointer to the …pointer which points to the actual data.

Get back with the previous example above; if you want s2 to point to the same data as s1, here is what you can do with reference:

let s1 = String::from("hello"); // (1)

let s2 = &s1; // (2)

s1is now valid and be declared as the owner ofString::from("hello")The

&represent references, this allows2refer to same data ofs1without taking the ownership ofs1→ We can call the action of creating a reference borrowing:

s2is borrowing theString::from("hello")froms1

Outro

The automatic reference count + garbage collector in Python makes it easier for users to write code.

However, running the background garbage collector surely slows down the program.

On the other side, Rust forces users to apply the ownership principles, which provide more explicit and fine-grained control over memory management. However, this might increase the time for the user to write the right code (which is determined by the Rust compiler).

Besides the garbage collector (Python, Java…) and ownership (Rust) approaches for memory management, C++ gives you the most freedom regarding memory control: you can manually declare the memory you need with a pointer and new/delete operators.

Developers have control over memory allocation and deallocation. Still, they must be cautious to avoid common pitfalls like memory leaks (unused memory is not free) and dangling pointers (pointer point to nothing).

Rust also allows you to manage the memory manually, like C++, but it may be for the future post.

Before you leave

Leave a comment or contact me via LinkedIn or Email if you:

Are interested in this article and want to discuss it further.

Would you like to correct any mistakes in this article or provide feedback?

This includes writing mistakes like grammar and vocabulary. I happily admit that I'm not so proficient in English :D

It might take 3 minutes to read, but it took me more than three days to prepare, so it will motivate me greatly if you consider subscribing to receive my writing.

What are tools you used to write the articles and drawings?

Good informative article. Im also in FOMO mode. Any recommendations on starting RUST journey?